A “Capital Recession” is Intensifying as Debt Ceiling Discussions Continue

The U.S. is in a “Capital Recession”

- No two recessions are identical. Commonly understood as two quarters of negative real GDP growth, recent recessions have come in various forms - from job losses to credit crunches. Hard landing, soft landing, or somewhere in between - what we are undergoing today is best characterized as a “capital recession”. The free flow of capital, enabled by a prolonged period of zero interest-rates, is today constrained by far higher rates and tightening in lending terms.

- Financial to real assets across the risk spectrum - from public equities to bonds and residential to commercial real estate - are witness to a drastic shift in sponsorship. As assets change hands, the current regime forces a revaluation of assets. We are well into this process, the onset of which was the Fed’s rate hikes and Quantitative Tightening (QT). No asset across the quality spectrum has been spared, not even “risk-free” Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities.

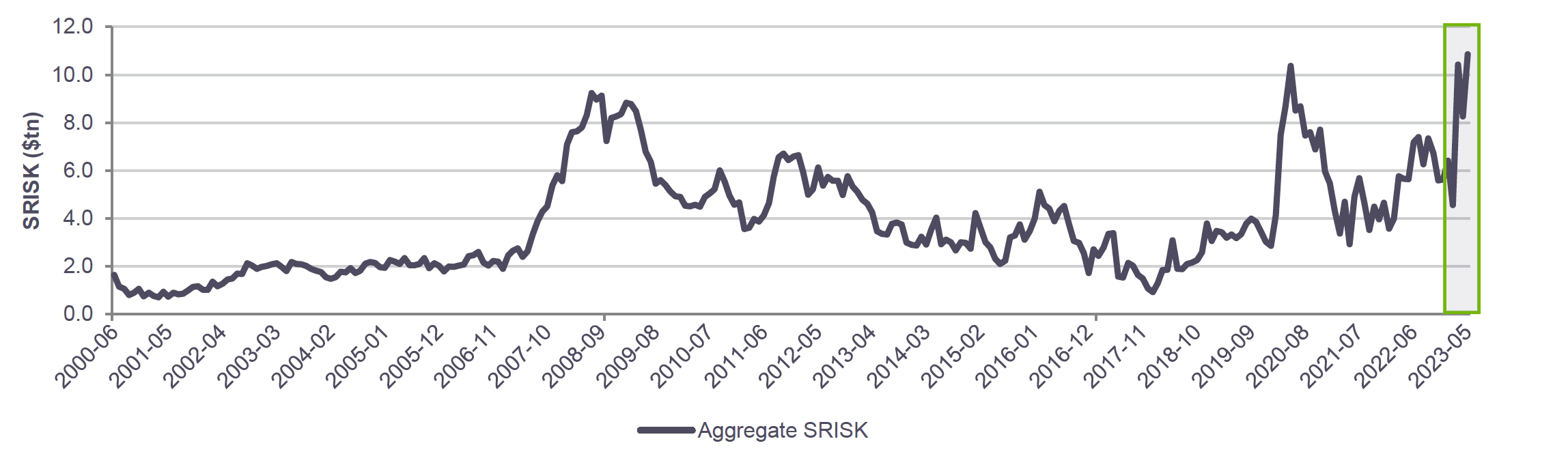

- Moreover, recent bank failures show building stresses, exposing a growing capital vacuum. By one stress indicator of systemic risk, NYU Stern’s V-Lab SRisk indicator shows $550bn of capital shortfalls developing since just prior to the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. The SRisk is a measure of U.S. public bank and non-bank entities capital position, as implied by market prices.

- This structural shift in shift in lending capacities has already put the U.S. into a “capital recession.”

$550bn Shift in Public Bank, Non-Bank Capital Shortfall Since SVB's Collapse(1)

Getting Through the Debt Ceiling

- Market pricing and the comments of most observers imply a baseline view that a deal will get done to raise or suspend the debt ceiling prior to a default. Equity volatility ought to be higher and prices lower if the risk of a default was perceived to be high by market participants. The basis of this view is that a default would be so catastrophic for markets, Congress and the White House cannot let it happen.

- In addition to the damage a default would cause to the full faith and credit of the U.S. government (also the reserve currency), the ripple effects through the financial system would likely be devastating. For example, in the event of a default, would Treasuries still be acceptable collateral for derivative agreements or Fed liquidity programs? Negotiations are likely to go to the 11th hour as the parties seek to exert maximum pressure, but the “X Date” is uncertain.

- In 2011, the Treasury was within two days of defaulting before a deal was reached. Should the U.S. government default, the Fed would likely not cut interest rates because this action would in no way offset the disruption to markets. Instead, the Fed would likely focus on the plumbing of the financial system and liquidity measures to support the market functioning.

- Counter-intuitively to many, the run-up in 10-year U.S. Treasury yields into the debt-ceiling agreement on 31 July 2011, followed by the August 5th S&P ratings downgrade of the United States sparked a sharp rally.