Powell’s Jackson Hole Dilemma

The Rithm Take

The Kansas City Fed’s Monetary Symposium, which is held in late August at Jackson Hole (a location originally chosen to tempt then Fed Chair Paul Volcker, who was an avid fly fisherman, to speak at the conference), has been an important event for Fed Chairs to outline key aspects of economic policy. For example, in August 2001 Chair Greenspan set out his thinking on the role of asset prices and the wealth effect on economic growth. In 2012, Chair Bernanke made the case for another round of quantitative easing, and in August 2023, Chair Powell gave a short speech suggesting that real interest rates would have to stay higher for longer to defeat inflation.

Last year, Chair Powell affirmed his confidence that inflation was returning to the Fed’s 2% target rate, saying “our efforts to moderate aggregate demand, and the anchoring of expectations have worked together to put inflation on what increasingly appears to be a sustainable path to our 2 percent objective.” The speech was followed by a full percentage put reduction in the federal funds rate during the last four months of 2024, but these cuts were received poorly in the bond market as long-term interest rates moved higher.

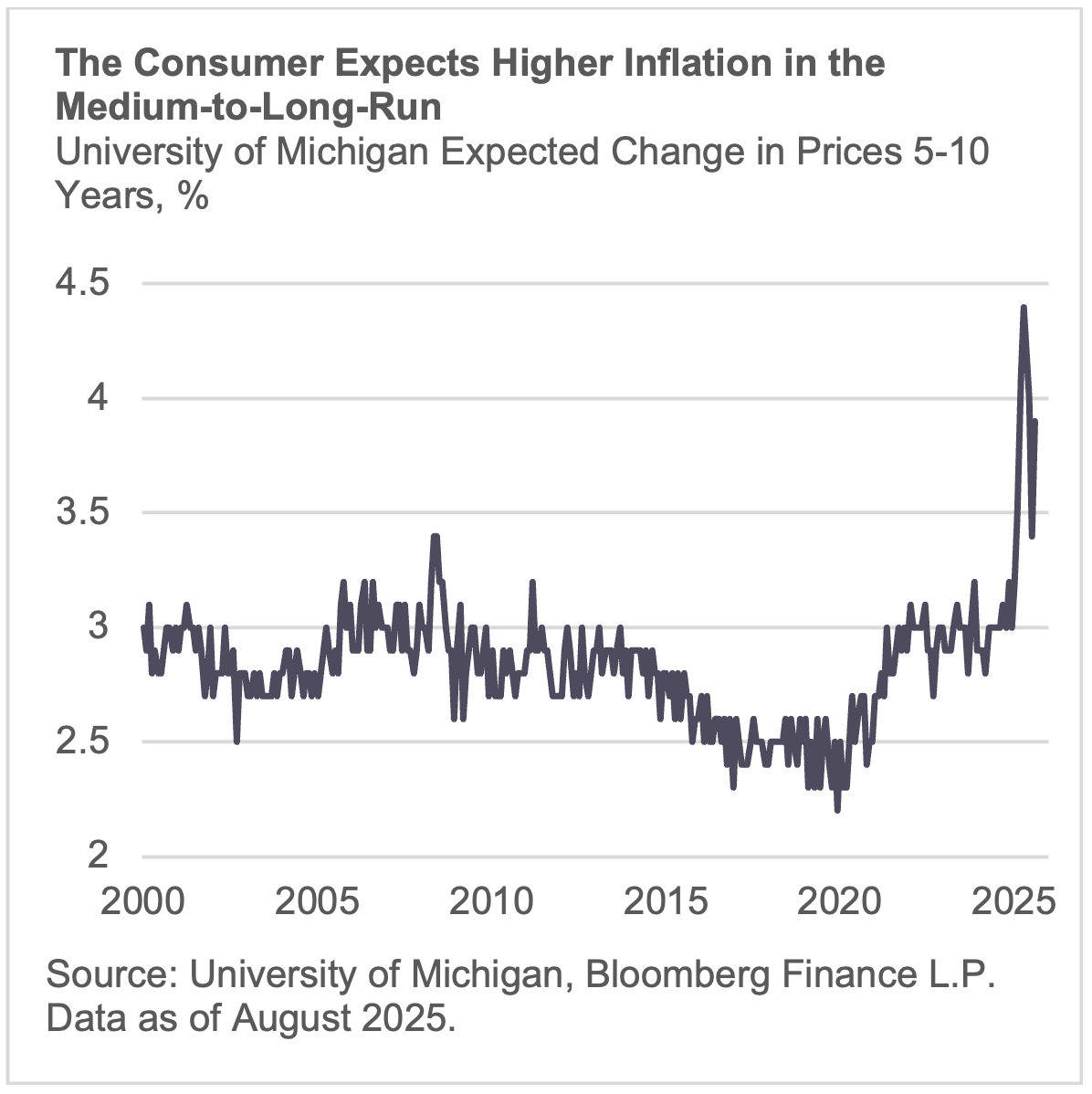

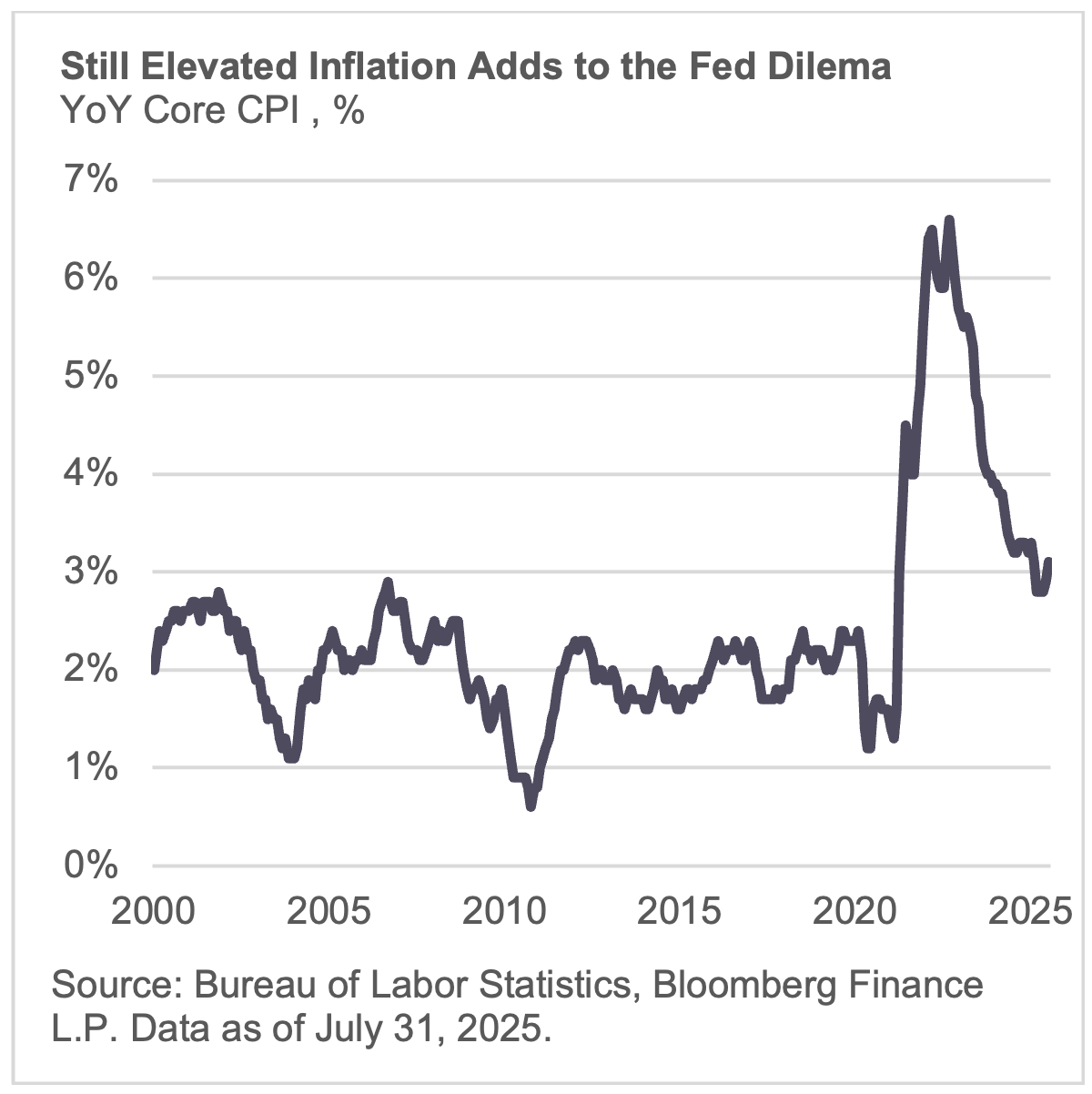

As Powell thinks about his Jackson Hole speech this year, he faces a quandary. The core inflation data are slowly moving away from the Fed’s 2% target, with core CPI inflation rising to 3.1% in July from 2.9% in June on a faster rate of increase in goods prices. Additionally, the July 0.9% increase in final demand PPI suggests that there is more price pressure to come. The medium-term inflation expectation from the University of Michigan jumped back up to 3.9% in August from 3.4% in July (it was 3.0% and stable when Powell gave his speech last year). Meanwhile, although nonfarm payrolls only increased at an average rate of 35,000 jobs per month over the last three months, the unemployment rate was unchanged at 4.2% over these three months, which is the Fed’s estimate of full employment. With uncertainty over the impact of tariffs yet to be resolved, the case to leave interest rates unchanged in September is a strong one. However, fed funds futures more than fully priced in a quarter-point cut on the day following the July CPI report, which shows that the market is looking for a rate cut on September 17. If Powell fails to disabuse this notion or at least lay down some strong conditions that need to be met for a rate cut, he might find himself being boxed in to acquiescing to a cut on September 17.

Market Signals

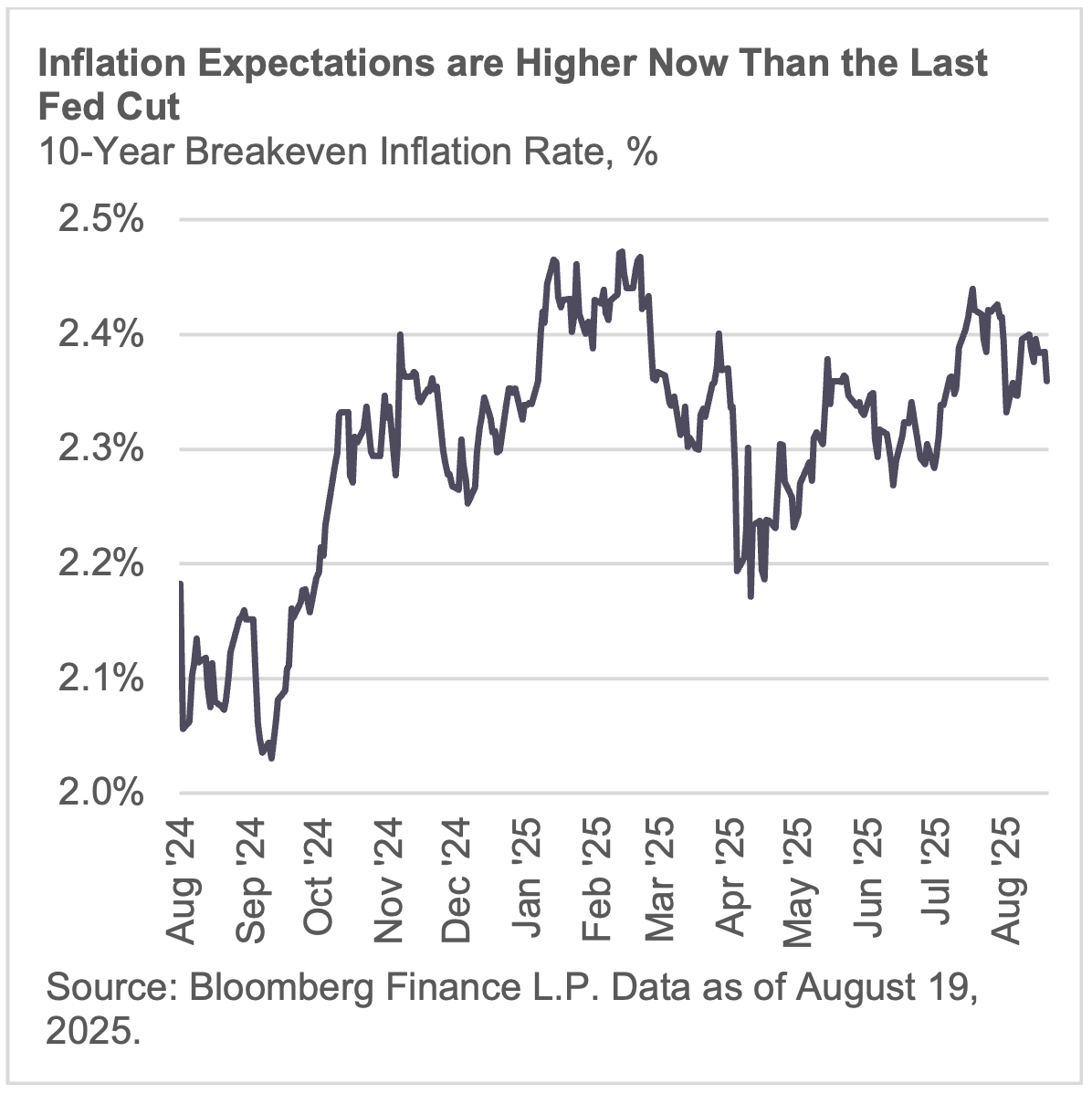

While the market still leans heavily towards a rate cut, the eventual reaction to the PPI, the 0.3% increase in nonfuel import prices in July, and the jump in medium-term inflation expectations in early August have caused the market to back off a little, now pricing in an 84% probability of a rate cut. This move allows Powell to argue that, unless the August inflation data show improvement in the outlook, the Fed has little reason to shift its stance. By September 17th, the Fed will have received CPI, PPI, import prices, and preliminary September medium-term inflation expectations. However, because these releases fall during the quiet period ahead of the FOMC meeting, the Fed will have no chance to guide market expectations. When the Fed cut interest rates by 50 basis points last September, 10-year inflation breakevens had fallen to around 2%. However, over the last year, this breakeven has risen to around 2.4%, which does not provide an encouraging signal to ease further.

The Conversation

The FOMC is more divided than it has been in recent years with Governors Waller and Bowman dissenting in July in favor of a rate cut, both of whom cited concerns about the labor market and argued for looking through the impact of tariffs, seeing them as having a one-off impact on prices. Combined with the slowdown in payroll growth, these dissents have tilted the market towards looking for a rate cut on September 17, which presents Powell with a dilemma. If he is inclined—as he has been— he likely will argue that the economy is solid and he needs more information to evaluate the impact of tariffs on inflation. The last set of FOMC projections (SEPs), which were made in June, showed the median number of rate cuts judged appropriate in 2025 was two. If Powell wants to cut rates—and to date he has not shown an inclination to do so—then he can say that he judges that policy would still be restrictive after a further quarter-point cut, and he is relatively confident that inflation will soon resume its trend back to 2%. However, with higher inflation expectations than a year ago and the full impact of tariffs a long way from being felt, if he believes that the Fed should continue to watch and wait, he needs to be resolute on Friday and say that he is disinclined to support a rate cut next month. If he doesn’t, he is likely to face an uncomfortable choice of either cutting rates or disappointing the market.