Fed Likely to Cut Rates Next Week; A Look at the Economic Backdrop

The Rithm Take

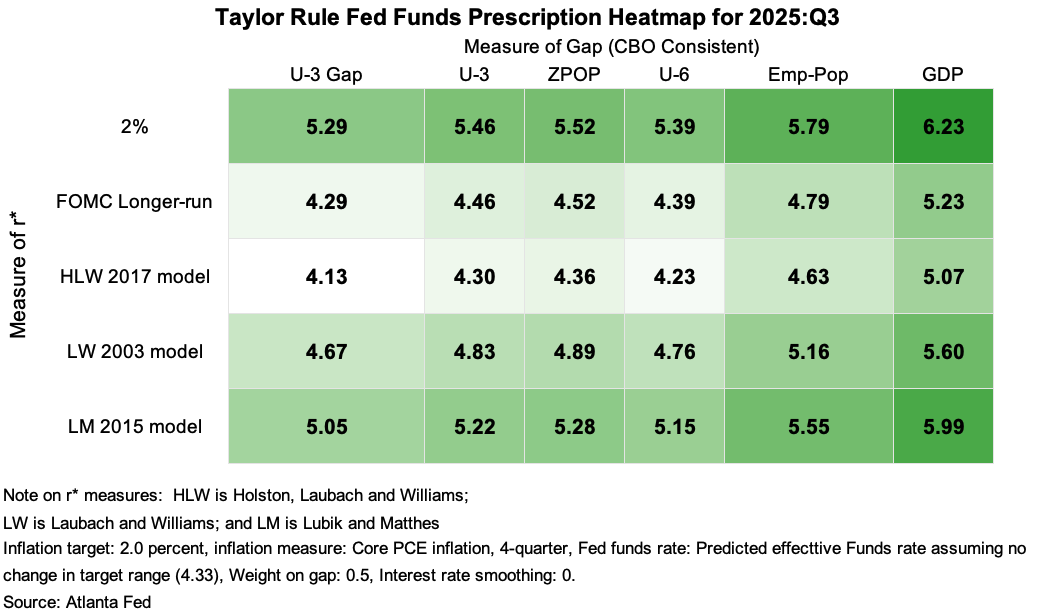

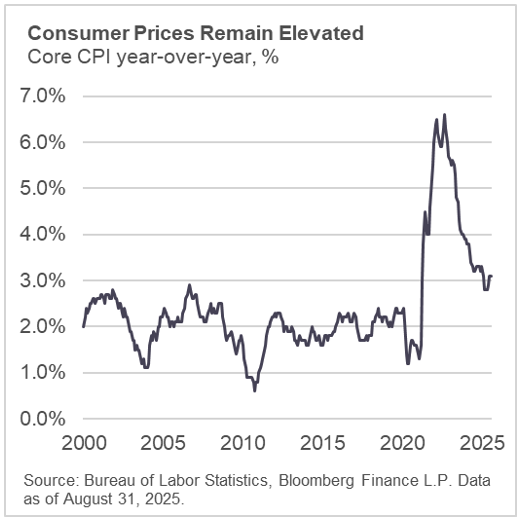

Chair Powell signaled at Jackson Hole in late August that he was open to a rate cut on September 17, which reignited expectations for a cut that is now fully priced into interest rate futures. The Powell Fed has, in the past, tended to align its decisions with market expectations when a cut was fully priced in immediately ahead of the meeting. However, core CPI inflation held at 3.1% in August and the three-month rate moved up to 3.6%. Job creation has slowed to an average pace of 29,000 per month in August but the unemployment rate at 4.3% is still only 0.1% point above the FOMC’s estimate of full employment. Moreover, the Atlanta Fed’s Taylor Rule utility shows 21 of the 30 models suggest policy is accommodative and none shows policy as restrictive. When the Fed’s dual mandates are in conflict, Powell has argued that the distance of each variable from its objective and the length of time it is expected to deviate from its target are the relevant considerations for setting policy and it is hard to make a case that employment should be the predominant concern at this point. Cutting rates when the case is far from clear risks accelerating the passthrough of tariffs into prices and increases the chances that tariffs may have a more persistent impact on inflation. In addition, the long end of the bond market did not react well to the one percentage point of rate cuts that were taken out between September and December of last year.

Economic Fundamentals

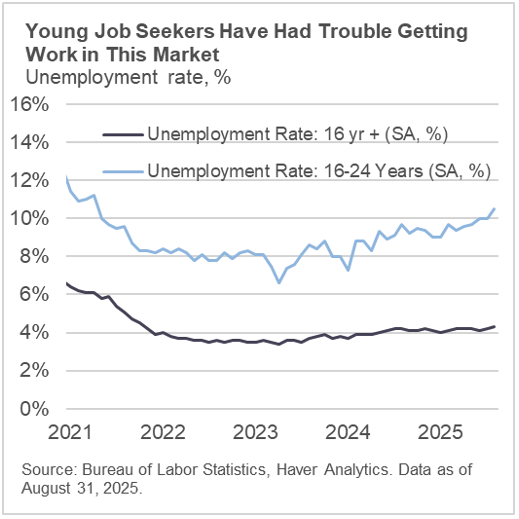

The Fed is tasked with maintaining price stability, which it has interpreted as a 2% inflation rate measured by PCE prices, and maximum employment, which the median estimate of the FOMC sees as an unemployment rate of 4.2%. The major challenge facing the attainment of 2% inflation is that disinflation has stalled out and tariffs are slowly being passed through, which is pushing up the underlying inflation rate. Using the August CPI data as a proxy for PCE prices, core inflation on a year-over-year basis was 3.1% and, over the last three months, the rate has been higher at 3.6%. Moreover, it still appears to be early days for inflation passthrough with the average tariff level in July, at 9.7%, being well below the rate of 17.4% that the Yale Budget Lab estimates will be the eventual average rate if current tariffs are left unchanged. It seems a relatively uncontentious statement that prices are headed higher but what is not clear at this point is whether this is a one-time shock to the price level or a more persistent rise in inflation. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate, at 4.3%, is only slightly above the Fed’s 4.2% estimate of full employment. Moreover, the breakeven pace of job creation is unclear given uncertainties about the impact of the Administration’s immigration enforcement policies. Over the last three months, the labor force has only risen by about 70,000 persons per month on average. As of the end of July, there is still almost one open vacancy per unemployed job seeker. Monetary policy has shifted attention away from inflation and towards jobs.

Net job creation has slowed not because of a rise in layoffs—these have been very steady at low levels—but because of a slowdown in hiring. At the same time, the economy is experiencing rising productivity growth. The rise in youth unemployment in recent months may reflect that potential new hires may not have the skills to compete with emerging technologies. In these circumstances, lowering interest rates may do little to boost employment growth and job creation but the easier monetary conditions that lower rates would signal could encourage firms to raise prices in the face of the cost shock from tariffs and in the reduced competitive environment that higher prices of imports is creating.

The Conversation

In normal times, the Fed has a difficult job with one servant—monetary policy—serving two masters—price stability and maximum employment. The Fed has built up significant credibility in recent years that its decisions, for the most part, are made in a technocratic and independent manner. This is not to say that the Fed has not misdiagnosed the economic ills and applied the wrong medicine as it did in arguing that the rise in inflation in 2021 was transitory and continuing to ease policy through large scale bond purchases. However, the experience of 2021 shows that continuing to ease monetary policy when economic conditions warrant a reduction in accommodation can fuel a rapid rise in inflation—particularly in the face of supply constraints. If those at the Fed are correct in arguing that the pass through of tariffs will be contained, that underlying inflation is set to fall back towards 2% in fairly short order, and that the labor market is weakening due to slowing demand, then a rate cut next week will be well timed. If, however, the economy is close to full employment, there are growing constraints on supply from tariffs and a shortage of labor with the skills employers need, and that underlying inflation pressures are rising, then easing monetary policy will add fuel to this pick up in inflation. The risk here is that if inflation pressures continue to pick up after the cut, then market participants may begin to lose confidence in the Fed’s commitment to price stability, which could put upward pressure on long-term yields.