Collateral Control Failures: What First Brands and Tricolor Reveal about ABF Oversight

Key Takeaways

- First Brands (auto parts supplier) and Tricolor (subprime auto dealer-lender) both failed in 2025, generating significant losses for “secured” asset-based lenders despite formally collateralized structures.

- In both cases, initial leverage and liquidity stress exposed deeper issues: borrowers retained full control of cash and reporting, collateral oversight was weak, and allegations emerged of misused, missing or double-pledged assets.

- Together they highlight a structural vulnerability in credit: asset-backed facilities can behave like unsecured risk when lenders rely on borrower data and fragmented infrastructure rather than real control of collateral and cash flows.

- A more resilient approach centers on clear proof of ownership, direct influence over how and where payments are made, independent oversight of servicing, and continuous, asset-level verification of what is actually owned and being paid.

Introduction

The First Brands Group and Tricolor Holdings failures in 2025 highlight a common theme across otherwise distinct credit situations: large, collateral-backed facilities were extended on the assumption of secured, self-liquidating exposures, but lenders did not maintain sufficient operational control over either the underlying assets or the cash they generated.

In both cases, lenders relied on:

- Borrower-produced borrowing-base reports rather than independent, bank-controlled data

- Imperfect or fragmented registry systems that do not operate at the asset-ID level

- Structures in which the borrower acted as its own servicer and gatekeeper of collections

The underlying issue in both situations is lender control, not asset class. The failures sit in sectors—aftermarket auto parts and subprime auto finance—that have long been considered “understandable” for asset-based lenders.

The weak point was not complexity of product, but the absence of a consistent control stack around ownership evidence, cash-flow control, servicing oversight and continuous verification.

First Brands – Leverage, Receivables and Control Gaps

I. Capital Structure and Liquidity Pressure

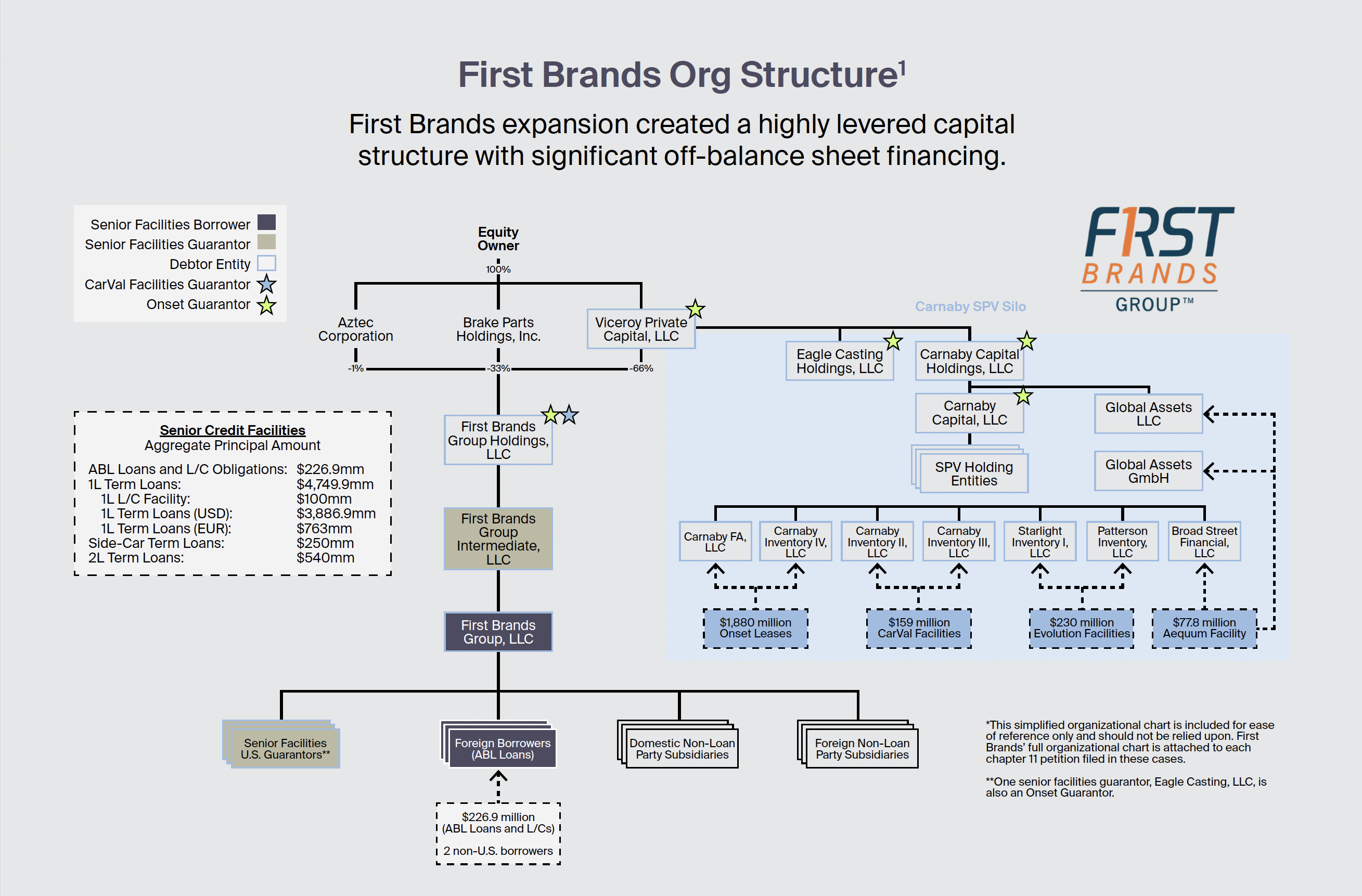

First Brands Group, a major autoparts supplier built through a roll-up of manufacturers and distributors, entered 2025 with over $10 billion of total debt and approximately $900 million per year in interest obligations.1 The business grew quickly by acquiring multiple auto parts companies with borrowed money.

The capital structure depended on stable aftermarket demand and synergy execution. That assumption broke down when:

- U.S. import tariffs increased raw-material and component costs

- Integration and restructuring expenses associated with the roll-up remained elevated

Operating cash flow fell sharply. Management pursued a refinancing to extend maturities and stabilize liquidity. Prospective lenders, however, raised accounting and quality-of-earnings concerns focused not only on operating performance but also on the structure and reporting of First Brands’ receivables and inventory financing programs.2

1 Source: In re: First Brands Group, LLC, et. al., Case No. 25-90399 (CML) (Bankr. S.D. Tex. Sept. 29, 2025), Docket # 22 at 17.

2 Source: Docket # 22 at 34-40, supra; In re: First Brands Group, LLC, et. al., Case No. 25-90399 (CML) (Bankr. S.D. Tex. Sept. 30, 2025), Docket #55 at 7-9; Business Wire, First Brands Group Receives Court Approval to Immediately Access $500 Million of $1.1 Billion in Debtor-in-Possession Financing,” Oct. 2, 2025.

II. Default and Chapter 11

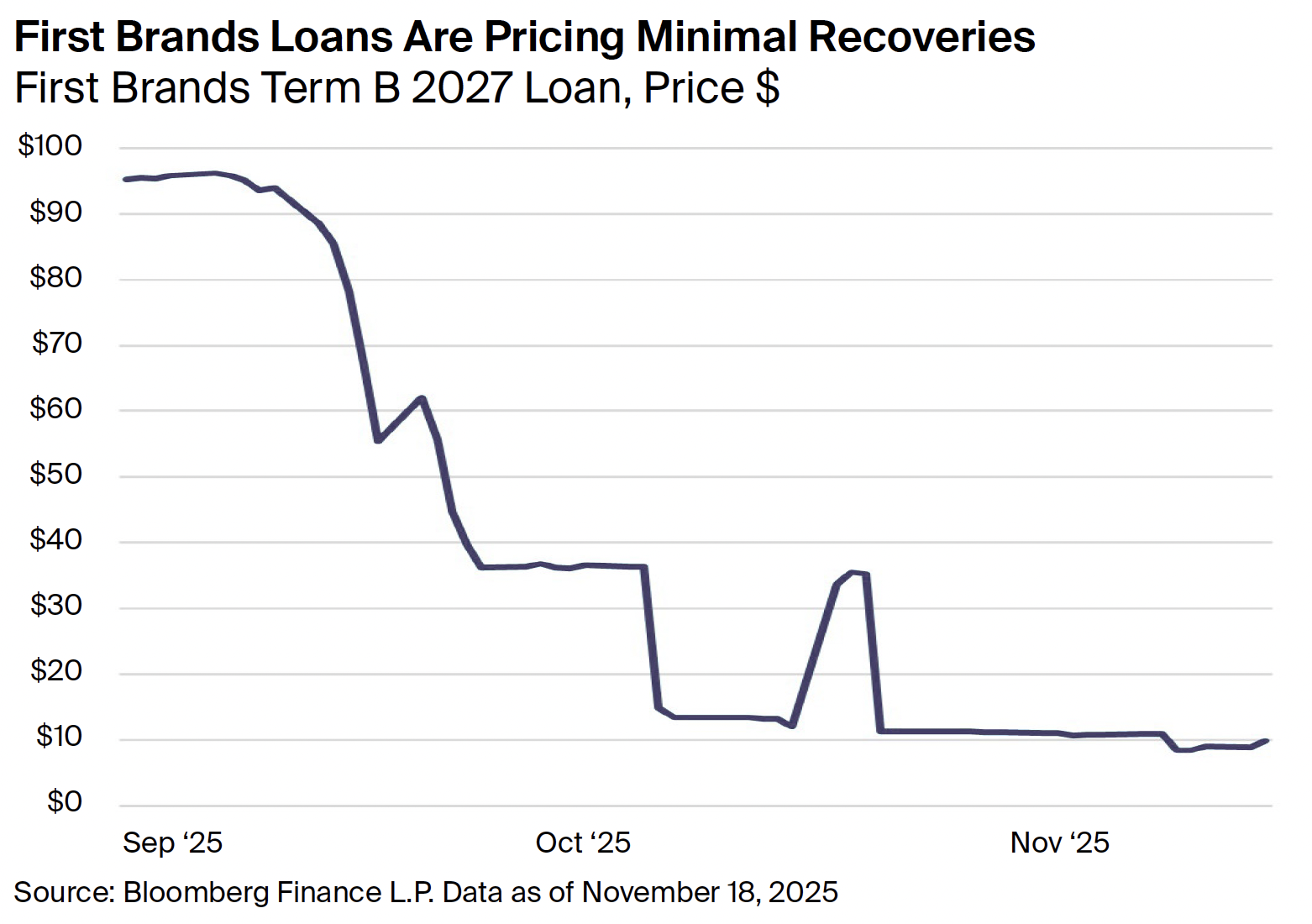

By late September, First Brands defaulted on a $1.9 billion inventory financing facility.2 Secured banks exercised set-off rights and swept remaining cash. The company was unable to meet payroll and other near-term obligations and filed for Chapter 11 on September 29, 2025, supported by approximately $1.1 billion of debtor-in-possession (DIP) financing to maintain limited operations.1

At that point, the immediate cause of failure appeared to be a liquidity breakdown driven by an over-levered capital structure. Subsequent disclosures reoriented attention toward how the company’s receivables and inventory financing structures had been designed and operated.

III. Receivables and Financing Mechanics

First Brands engaged in multiple receivables financing and factoring arrangements, including facilities where vehicles managed by Jefferies and Raistone advanced cash against invoices owed by major retailers.2,3 The mechanics were standard:

- The operating business generated invoices to large, creditworthy retailers

- Financing vehicles purchased or lent against those invoices at a discount

- When retailers remitted payment, those funds were intended to flow to the financing vehicles to repay advances

In well-controlled structures, three safeguards typically work together to prevent diversion and duplicate financing:

Deposit Account Control Agreements (DACAs):

Under UCC §9-104, a secured party has “control” of a deposit account when the bank agrees to follow that party’s instructions regarding disposition of funds without further consent from the borrower. In many First Brands programs, retailers continued to remit payments into operating accounts controlled by the company, rather than into accounts governed by DACAs.2 In effect, lenders owned receivables on paper but did not control the incoming cash.

Customer Payment Notifications (Direct-Pay under UCC §9-406):

When receivables are sold or assigned, account debtors should receive formal notice that, from that point forward, payment to the assignee is required to discharge the obligation. In certain First Brands programs, these notices were allegedly delayed or not sent.2,4 Retailers continued to pay First Brands directly, and lenders depended on borrower-generated reports to track repayment.

Invoice-Level Identification and Duplication Controls:

UCC-1 filings perfect security interests over categories such as “all present and future receivables” but do not identify individual invoices. There is no national registry of receivable IDs. Without an invoice-level registry or independent tie-out, two lenders can believe they have first claim over what is effectively the same cash flow if both rely solely on borrower-certified borrowing-base schedules.4

Because First Brands acted as its own servicer—collecting customer payments, applying cash internally and remitting to various facilities—the integrity of the structure relied heavily on internal controls and reporting.

3 Source: In re: First Brands Group, LLC.

4 Source: Raistone Capital examiner-motion allegations in In re First Brands Group, LLC, Case No. 25-90399 (Bankr. S.D. Tex.), as reported in coverage of roughly $2.3 billion of “vanished” receivables and commingling of payments.

IV. Creditor Allegations and Regulatory Interest

As the case progressed, creditor filings and lender disclosures widened the narrative beyond liquidity and leverage:

- A Jefferies/Leucadia-managed vehicle disclosed approximately $715 million of exposure to First Brands receivables3

- Raistone petitioned the bankruptcy court to appoint an independent examiner, alleging that roughly $2.3 billion of receivables “vanished” through commingling and diversion of customer payments owed to multiple funding partners4

- A preliminary U.S. Department of Justice inquiry reportedly began focusing on off-balance-sheet misrepresentation, duplicate pledging and the accuracy of CEO-signed borrowing-base certificates5

Civil complaints and examiner materials have tied certain practices—cash-application delays, invoice re-aging and reuse of receivables across overlapping facilities—to directives associated with senior leadership.4,5 Allegations include the execution of borrowing-base certificates that did not accurately reflect collateral quality.

Whether or not these allegations are ultimately proven, the pattern is clear from a lender perspective:

- Borrower-controlled cash accounts and servicing created scope for commingling and delayed remittances

- Absence of DACAs and consistent direct-pay notices meant lenders lacked direct control over collections

- No invoice-level registry or daily tie-outs allowed potential double-pledging or reuse of receivables without timely detection

First Brands illustrates how unsustainable leverage can be amplified by structural weaknesses in collateral and cash control, and how those weaknesses can be exploited under stress.

5 Source: Reuters, “US justice department launches inquiry into First Brands,” Oct. 2025 (Justice Department probe into First Brands’ receivables and borrowing-base practices).

Tricolor – Auto Collateral, Double-Pledging and Fragmented Titles

I. Business Model and Capital Structure

Tricolor Holdings, Inc., headquartered in Texas, operated as a vertically integrated used-car dealer and subprime auto lender under the Tricolor and Ganas Auto Group brands.6 The company specialized in selling and financing vehicles for borrowers with limited or no credit history, extending retail installments contracts through its captive lending arm.

To support this model, Tricolor utilized:

- Warehouse lines secured by pools of consumer auto loans

- Floorplan facilities secured by vehicle inventory on dealer lots

- Asset-backed securitizations (ABS) backed by seasoned receivables

Lenders included institutions such as Fifth Third Bank and JPMorgan Chase.7,8 Fifth Third later disclosed an expected impairment of approximately $170–$200 million tied to “alleged external fraud at a commercial borrower,” widely understood to be Tricolor.7

II. Auto Title Infrastructure and Operational Blind Spots

Unlike receivables, auto collateral is anchored in state-level title systems:

- Vehicle titles and liens are administered by 50 state DMVs, each with its own databases, formats and processing timelines

- Some states operate electronic lien and title (ELT) systems; others rely heavily on paper documentation

- Vehicles can be retitled across states, and NMVTIS (the National Motor Vehicle Title Information System) provides only partial, non–real-time consolidation8

Within this fragmented infrastructure, it is operationally permissible for multiple liens to exist over the life of a vehicle. For example:

- A dealer’s floorplan lender finances inventory and holds the lien while the car is on the lot

- Once sold and financed, a retail lender (captive or third party) records a new lien to secure the consumer installment contract

- If the dealer fails to repay the floorplan lender at sale, the vehicle is “sold out of trust” (SOT): the consumer lender appears as lienholder on title, but the floorplan lender remains unpaid and unsecured

In an integrated dealer–lender model like Tricolor’s, with multiple lenders funding different parts of the chain and the platform itself acting as servicer, the potential for inconsistencies and misuse is significant unless VIN-level reconciliations and independent controls are in place.

III. Failure Dynamics

Initial findings reported by lenders and in court filings indicate that Tricolor:

- Pledged the same consumer auto-loan portfolios to more than one financing partner, creating overlapping claims on identical collateral pools

- Maintained ledgers and borrowing bases that could not be reconciled across warehouse and ABS facilities

- Exhibited missing vehicles and classic “sold-out-of-trust” patterns where floorplan-funded inventory was not repaid at sale8

As lenders compared borrowing-base data, confidence in the integrity of collateral and reporting eroded quickly. Facilities were frozen. With cash flow interrupted and the legal status of loan portfolios in dispute, Tricolor bypassed a restructuring path. On September 10, 2025, the company filed directly for Chapter 7 liquidation, indicating that lenders and management saw no viable path to reorganize around the existing asset base.6

Regulatory and policy responses have focused on the inadequacy of:

- VIN-level audit controls for dealer–lender platforms

- NMVTIS feeds and their ability to surface duplicate or inconsistent title records in a timely manner

- Structural protections in warehouse and floorplan facilities where the dealer is also the servicer and cash collector

The Tricolor case demonstrates how quickly secured auto exposures can become uncertain when lien records, VINs, inventory and loan tapes are not reconciled in a disciplined, high-frequency manner.

6 Source: In re Tricolor Holdings, LLC, Case No. 25-33487 (Bankr. N.D. Tex., Dallas Div., filed Sept. 10, 2025) – Chapter 7 petition and case docket.

7 Source: Fifth Third Bancorp, “Current Report (Form 8-K),” filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission on September 9, 2025.

8 Source: Barron’s, “Tricolor Files for Bankruptcy. The Auto Lender Was Once an ESG Favorite,” Sept. 2025; Financial Times, “JPMorgan and Fifth Third face losses tied to collapsed subprime car lender,” Sept. 2025 and DOJ/AAMVA materials on NMVTIS and state DMV/ELT title-lien practices.

Common Themes – When Lenders Don’t Control Collateral or Cash

Across First Brands and Tricolor, the core failure modes are consistent despite differences in asset type and legal process.

Borrower-controlled servicing and collections:

In both situations, the borrower originated and serviced assets, collected payments and controlled when and how those funds reached financing partners. That model embeds an inherent conflict in stress scenarios: the same party responsible for reporting collateral and cash is also under pressure to preserve operating liquidity.2,4,6

Reliance on borrower-generated borrowing bases:

Some lenders depended on monthly borrowing-base certificates and periodic reports prepared by the borrower. Verification was largely retrospective and sample-based (field exams, audits, lot inspections) rather than continuous and data-driven. In fast-moving portfolios and inventories, this left wide intervals during which assets could be moved, reused or diverted without detection.2,4,8

Registry and infrastructure limitations

- Receivables: UCC filings perfect interests in categories, not specific invoices. Without an external invoice-level registry or system, duplicate pledging or reuse rests on borrower honesty and internal controls.4

- Autos: state DMV and ELT systems, combined with NMVTIS, do not form a unified, real-time national registry. Cross-state retitling, processing delays and data gaps can create visibility gaps even where liens are properly recorded.8

Incentives favoring deployment over control:

Some lenders and platforms face strong incentives to deploy capital, move quickly and accommodate bespoke borrower needs. Investing in operational controls—DACAs, lockboxes, independent custodians, daily reconciliation engines—is resource-intensive and less visible in marketing. As a result, documentation and legal form often outpace the operational infrastructure needed to enforce them under stress.

The result is that facilities may appear “secured” and “self-liquidating” in documentation, while in practice they depend significantly on borrower integrity and system functionality. That dependency is not always explicitly recognized in pricing or risk budgeting.

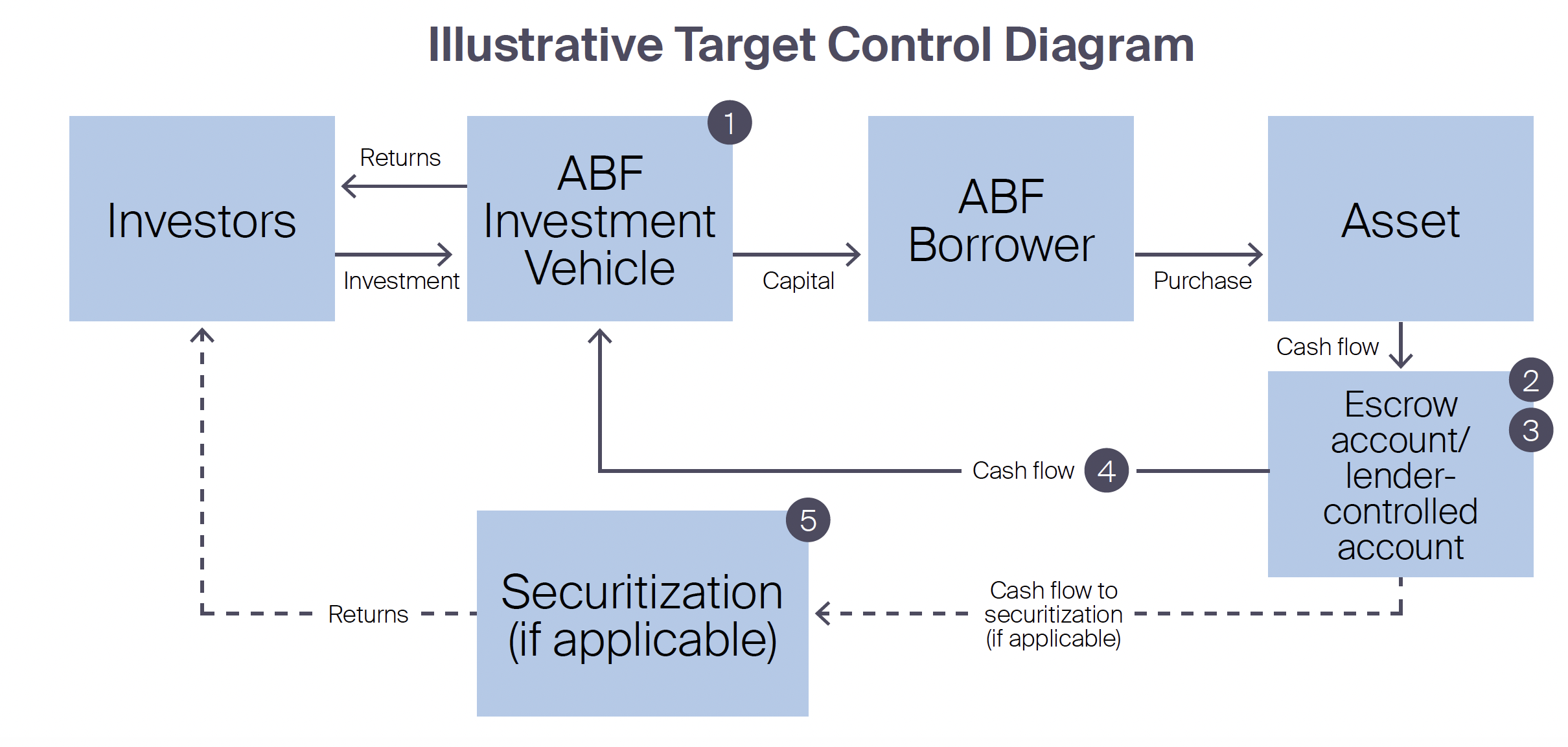

Cross-Asset Operational Guardrails – A Control Stack

The recurring patterns in First Brands and Tricolor are not asset-class specific. They reflect gaps in ownership evidence, cash-flow control, servicing oversight and continuous verification. A lender that does not originate or service assets can still mitigate much of this risk by embedding a portable control stack into each facility. The illustrated control stack is not necessarily new to those active in the public securitization markets and is one that the emerging private ABF sector requires.

1. Ownership Evidence and Perfection

The first step is to ensure that the facility (or its SPV) can enforce what it has funded:

- Execute assignments and endorsements so that the funding vehicle qualifies as the “person entitled to enforce” the note where Article 3 applies (UCC §3-301)

- Use the appropriate perfection method for each collateral type:

- Real-property liens recorded in land records

- UCC-1 filings for receivables and payment intangibles (UCC §9-310)

- Control or possession where required by Article 9 (e.g., deposit accounts under UCC §9-104)

- Utilize available registries—MERS for mortgages, DMV/ELT with NMVTIS reconciliation for vehicles—to create a traceable chain of title and lien priority2,4,8,9

2. Cash-Flow Control

Ownership on paper is insufficient if the borrower controls all collection channels:

- Route borrower and obligor payments to accounts subject to DACAs or trustee lockboxes that allow unilateral redirection or sweeping of funds once agreed triggers are hit (consistent with UCC §9-104 control mechanics)

- Provide direct-pay notices to account debtors and obligors so that, after assignment, they discharge obligations only by paying the assignee or its agent (UCC §9-406)9

These mechanisms shorten the distance between a covenant breach and actual control over cash.

3. Servicing Oversight

When the lender is not the servicer:

- Keep paper notes, titles and key documents with independent custodians or in compliant e-vaults

- Require servicer trust accounts with daily visibility for the lender or trustee, including loan-level remittance files

- Appoint a master servicer or collateral administrator with authority to oversee subservicers, aggregate and reconcile data and enforce uniform remittance standards

- Build data rights and backup-servicing triggers into contracts, tied to reporting lags, error rates and covenant breaches

This approach preserves operational continuity if performance deteriorates or servicer behavior changes.

4. Continuous Verification

Monthly attestations are not sufficient when balances and statuses change daily:

- Perform daily tie-outs between collections and positions at the unique ID level: mortgage MINs, VINs, contract or account IDs

- Reconcile internal records regularly against external data—lien filings, MERS, DMV/ELT and NMVTIS—to identify potential double-pledging, retitling or off-system activity2,4,8,9

- Use automated exception

5. Bankruptcy-Remote Transfer Mechanics

Where assets are funded through SPVs or purchased outright:

- Obtain true-sale opinions to support legal separation of assets from the seller in its insolvency

- Where relevant, obtain non-consolidation opinions so that SPVs are less likely to be substantively consolidated with the originator’s estate

Legal isolation does not replace operational controls, but it provides that those controls remain relevant if the originator fails.

While the control stack is portable, implementation varies by asset class.

9 Source: Uniform Commercial Code Articles 3 and 9 (official text and comments).

10 Source: Joshua Stein, Loan Assignments Primer, joshuastein.com

11 Source: Property Records Industry Association, eNote White Paper, pria.us

12 Source: Epperson Law, Assignment of Mortgages and MERS Practices, eppersonlaw.com

13 Source: Miller Nash, It’s Not Nice to Pay an Invoice Twice: Payment Demands During COVID-19 by Assignees of Accounts, millernash.com

14 Source: U.S. Department of Justice, National Motor Vehicle Title Information System (NMVTIS) Overview, vehiclehistory.bja.ojp.gov

Lender Protections Vary Across Asset Types

Mortgages9,10,11,12

| Mechanism | Description | Control Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Assignment of Mortgage | Record the transfer so public records (and MERS, if used) show the new owner/servicer (county land records; MERS registration via a Mortgage Identification Number). | Create a visible chain of ownership and priority so others can’t claim the lien. |

| Endorsement & Delivery of the Note | Make sure the loan’s IOU is signed over and the original (or authoritative e-note) is in the right hands (the holder must be the “person entitled to enforce,” UCC 3-301). | Ensure the lender can actually enforce the debt in court. |

| Custody of Original Note | Keep the original note/e-note with an independent custodian/e-vault (supports enforceability under Article 3 practices). | Avoid disputes about who can enforce; allow fast transfer if servicing changes. |

| Perfection of Security Interest | Record the mortgage in the land records (real-property perfection by recording; related personal-property rights follow UCC Article 9 where applicable). | Lock in priority against third parties. |

Consumer9,13

| Mechanism | Description | Control Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Assignment of Receivables | Sign a sale/assignment that actually transfers the right to payments (UCC Article 9 framework for accounts/payment intangibles). | Make ownership of the receivables clear and enforceable. |

| Borrower Notification (as applicable) | Tell borrowers where to send payments; after notice, they must pay the assignee to be discharged (UCC 9-406). | Stop misdirected payments; align legal discharge with the correct payee. |

| Perfection by Filing (UCC-1) | File a financing statement to perfect interests in receivables/payment intangibles (UCC 9-310 general rule). | Establish priority versus other creditors. |

| Servicing Agreement / Records Custody | Put data/audit rights and successor-servicer triggers in the contract; keep records under controlled custody (market standard to preserve ownership evidence). | Maintain operational control over the evidence of ownership. |

Auto9,14

| Mechanism | Description | Control Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Assignment of Retail Installment Contracts; Note Endorsement (if negotiable) | Transfer the payment right and, where applicable, endorse/hold the note so the enforcer is the legal holder (UCC 3-301). | Ensure the right party can enforce the auto loan. |

| Perfection of Security Interest in Vehicle | Put the lien on the vehicle title with the state and use ELT where offered (electronic perfection/update/release with DMVs). | Create a public, state-verified claim on the car. |

| Custody of Title / Lien Notation | Hold the paper or e-title listing the lender’s trustee/agent as lienholder (state DMV/ELT practice). | Block competing claims and speed recoveries on default. |

| NMVTIS Reconciliation | Check the national title database to catch washed/duplicate titles and cross-state retitling risk (NMVTIS). | Reduce fraud and duplicate-pledge risk tied to title manipulation. |

Conclusion

First Brands and Tricolor were not failures of exotic instruments. Both involved familiar asset types and credit structures. The core lesson is that legal form—secured, self-liquidating, asset-based—does not guarantee outcome if lenders do not build and maintain operational control over the ownership, cash flows and verification of their collateral.

Embedding a portable control stack across facilities, and tailoring it to the mechanics of each asset class, can materially reduce the risk that the same cash flow is financed twice or that pledged collateral is missing when stress hits. The operational effort required is significant, but the alternative—relying on trust where control is feasible—carries its own, now very visible, cost.

Receive the full publication in your inbox

Contact Us

For more information, contact Rithm’s Client & Product Solutions Team at cps@rithmcap.com.

Important Information

This material described herein is provided for informational purposes only. It may not be reproduced or distributed except as contemplated herein. The information contained herein is not intended to be taken by, and should not be taken by, any individual recipient as investment, legal, accounting, tax or other professional advice, a recommendation to buy, hold or sell any security, or an offer to sell or a solicitation of offers to purchase any security; no fiduciary, advisory or client relationship is created through this material.

This material is not and does not contain an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any security, including any security described herein or any security in any fund, and may not be relied upon in connection with the purchase or sale of any security. There can be no assurance if or when Rithm Capital Corp. (together with its subsidiaries, “Rithm” or the “Company”) or any of its affiliates will offer any security or the terms of any such offering. Any such offer would only be made by means of formal documents, the terms of which would govern in all respects. You should not rely on these materials as the basis upon which to make any investment decision. Moreover, wherever there is the potential for profit there is also the possibility of loss and investors may lose all or a substantial portion of their investment.

The source of all information contained herein is Rithm, unless otherwise noted. Some of the information contained herein has been obtained from third-party sources. Rithm has relied on the accuracy of such information and has not independently verified its accuracy. Rithm makes no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, fairness, reliability or completeness of the information contained herein. Certain economic and market conditions contained herein have been obtained from published sources and/or prepared by third-parties and in certain cases has not been updated through the date hereof. Rithm does not undertake any obligation to update such information.

Certain of the information contained herein is based in part on hypothetical assumptions and projected performance. Such results are presented for illustrative purposes only and are based on various assumptions, not all of which are described herein. Actual performance may vary materially.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results and should not be relied upon for any reason.

For information about Rithm’s business, including risks and financial information, please refer to our most recent Annual Report on Form 10-K and our recent Quarterly Reports on Form 10-Q filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”).

Legal Notice and Disclaimers

Certain statements in these materials may constitute forward-looking statements within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, which statements involve substantial risks and uncertainties. Such forward-looking statements (including estimates, opinions or expectations about any future event) are based on certain assumptions, discuss future expectations, discuss market outlooks or market expectations, describe future plans and strategies, include management’s beliefs and expectations, contain projections or estimates of results of operations, cash flows or financial condition or state other forward-looking information. These estimates and assumptions are inherently uncertain and are subject to numerous business, industry, market, regulatory, geo-political, competitive and financial risks that are outside of Rithm’s control. There can be no assurance that any such estimates and assumptions will prove accurate, and actual results may differ materially, including the possibility that an investor may lose some or all of any invested capital. The inclusion of any forward-looking statements herein should not be regarded as an indication that Rithm considers such forward looking statement to be a reliable prediction of future events and no forward-looking statement should be relied upon as such. Neither Rithm nor any of its representatives has made or makes any representation to any person regarding any forward-looking statements and none of them intends to update or otherwise revise such statements to reflect circumstances existing after the date when made or to reflect the occurrence of future events, even in the event that any or all of the assumptions underlying such forward-looking statements are later shown to be in error. For a discussion of some of the risks and important factors that could affect such forward-looking statements, see the sections entitled “Cautionary Statement Regarding Forward Looking Statements” and “Risk Factors” in Rithm’s recent Annual Report on Form 10-K and Quarterly Reports on Form 10-Q filed with the SEC, which are available on Rithm’s website (www.rithmcap.com).

Authors

Charles Sorrentino

Managing Director, Head of Investments

Satish Mansukhani

Managing Director, Investment Strategist

Alan Wynne

Senior Associate, Investment Strategist